Education • 11 min read

By Bitpanda

19.12.2025

Our first Mythbuster article was dedicated to demystifying cryptocurrency misuse. Fast forward 1 year, and we are coming back to the topic with some interesting updates. Let’s explore specific claims and arguments that were recently made by various authorities and institutional bodies. As always, we’ll present the situation objectively, offering perspectives and information that are often overlooked. Let’s take a closer look!

Over the past year, there have been persistent claims about the crypto industry being a major tool for money laundering (ML), terrorist financing (TF) and sanction evasion (SE), classifying it as high risk. This year also marks the establishment of the European Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA), which will centralise and enhance the EU and Member States' efforts to combat financial crime. Moreover, certain Crypto Asset Service Providers (CASPs) and issuers will fall under the AMLA’s purview. From the start, the authority labelled the crypto sector as an elevated risk. Other public agencies and stakeholders also provided similar assessments.

Let’s go through the main arguments from two key institutional bodies: the Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA) and Financial Action Task Force (FATF)

The AMLA Work Programme 2025, From Vision to Action, pointed out the following shortcomings:

The FATF in its June 2025 report echoed similar warnings:

Response to the high-risk labelling

Technological features, cross-border operations, and anonymity-enhancing capabilities

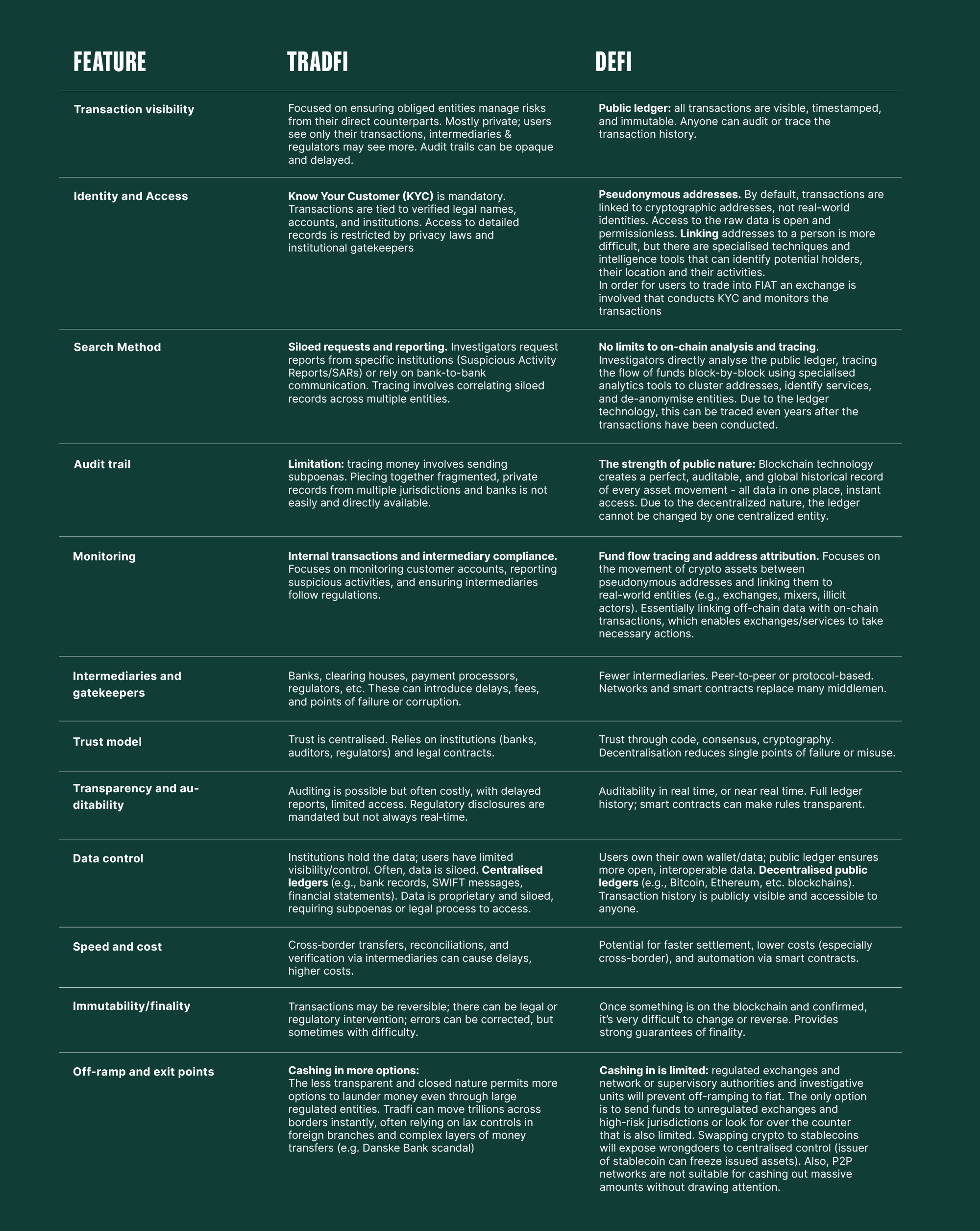

Every technology can be used for good and for evil. Traditional finance (TradFi), including cash, remittance, and bank transfers, has always been exposed to abuse and new methods of money laundering. Both crypto and TradFi have built-in mechanisms to prevent abuse. Additionally, sophisticated tools are being developed to support monitoring and exposing illicit actions. Contrary to statements from AMLA and FATF, the features of crypto and blockchain are not designed for illegal actors. Most importantly, their design is focused on strengthening and enhancing the digital economy and digital finance. Let’s compare both systems and see what their strengths and weaknesses are.

As we’ve shown, the transparency, record, accessibility and traceability of the crypto sector are unique compared with TradFi, which has inherent limitations. DeFi is an open and public network that anyone can access, which increases overall accountability.

There are plenty of negative arguments at the forefront that do not present the whole picture. Positive recognitions are, unfortunately, overlooked. For example, contrary to the criticism of AMLA and FATF, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), in its recent Bulletin no.111 titled: An approach to anti-money laundering compliance for cryptoassets (August 2025), outlines the advantages of blockchain technology:

“As the full history of transactions on the blockchain is publicly available, it could inform an assessment of how closely a particular unit of a cryptoasset is associated with past or current illicit activity. A diagnostic “AML compliance score” could be referenced in any further interventions by authorities when cryptoassets (including stablecoins) are presented for conversion to fiat currency at the “off-ramps” – notably, at the point of contact with the banking system.” (...)

“Crypto and stablecoins pose challenges to existing regulatory frameworks. These risks differ from those of traditional financial instruments, meaning the principle of “same risk, same regulation” does not apply (Aldasoro et al, 2025). An approach that takes account of the unique features of crypto and stablecoins and uses them to enhance regulation emerges as a promising avenue to close regulatory gaps.”

Obfuscation methods indeed make it more difficult and complex to leverage the features, yet they do not make detection impossible because a forensic trail always exists. Consequently, more efforts will naturally be placed into identifying the patterns of the obfuscation and to further enhance monitoring. Anything that can be associated or connected to an obfuscation mechanism can be black-listed or grey-listed as suspicious and shared with financial investigative units. Moreover, black market and laundering networks are under constant scrutiny as the transfers of assets can be linked to fiat exit/withdrawal points (crypto off-ramp to fiat). Therefore, we should see the obfuscation method as a speed bump instead of a deal-breaker. The inherent goal of cryptocurrency and privacy tools/features is to protect digital privacy and not to exploit it for illicit purposes.

There are various techniques and practices - to leverage transparency and traceability - that enable black or grey listing even when obfuscation was used, including:

Address clustering and graph analysis (on-chain);

Timing and value correlation (temporal/amount heuristics);

Transaction fingerprinting (pattern recognition);

Cross-chain and bridge tracing;

Cooperation with exchanges

Address tagging via on-/off-ramps and KYC data;

Metadata and off-chain intelligence;

Chain analytics + machine learning;

Legal/Regulatory actions and sanctions

OSINT data within monitoring tools, driven by exchanges

Privacy coins such as Monero (XMR) use advanced cryptography to conceal transaction details, but research and investigations show they are not completely infallible. Analysts can reduce anonymity through flaws in decoy selection, timing and network analysis, and by tracking movements between private and transparent addresses. Studies highlight that IP correlation and usage-pattern analysis can narrow anonymity sets, while intelligence work focuses on side-channel data and user behaviour rather than breaking the underlying cryptography. Although continuous upgrades strengthen privacy protocols, traces often remain detectable through combined on-chain and off-chain analysis. Exchanges can also actively decide what networks they want to offer, including technical implementations on blocking or quarantining or similar actions when privacy features are being used.

Colonial Pipeline ransomware seizure (2021) - the FBI traced the bitcoin ransom payment on the public blockchain to a specific address and used a seizure warrant to take control of ~ 63.7 BTC.

The Bitfinex hack recovery (2022) - In one of the largest single financial seizures in U.S. history, IRS Criminal Investigation and FBI agents used sophisticated blockchain tracing to follow Bitcoin stolen in the 2016 Bitfinex hack through layers of transactions, chain-hopping, and privacy services. Despite these obfuscation efforts, investigators were able to link the laundered funds to online accounts controlled by Ilya Lichtenstein and Heather Morgan — not only by on-chain analysis, but also by seizing a cloud-storage file that contained private keys for hacked wallets, as well as combining that with off-chain evidence like KYC records, darknet and exchange account data, and more.

The Silk Road seizures (2020–2021) — These cases showed how the immutability and transparency of the blockchain allow investigators to trace darknet-market–related Bitcoin, even after years. However, the large recoveries depended not just on on-chain tracing, but also on off-chain evidence — for example, KYC and IP data from exchanges, and a physical search of the hacker’s home. Despite the use of mixing services, these investigations highlight that privacy tools can slow down but not always fully prevent attribution when combined with other investigative methods.

Garantex shut down — In March 2025, the U.S. Secret Service, together with law enforcement from Germany and Finland, disrupted the Russian crypto exchange Garantex, seizing its domains and servers and freezing about $26 million in cryptocurrency. The Department of Justice unsealed indictments against two senior Garantex operators, including Aleksej Besciokov (who was later arrested in India). Blockchain analytics (e.g., Global Ledger) linked Garantex to a successor platform, Grinex, which allegedly continued much of the same business. In August 2025, the U.S. Treasury’s OFAC sanctioned Grinex as part of a broader action against Garantex-linked operations.

Stablecoins have drawn significant attention in discussions about financial crime, but the narrative around stablecoins driving criminal activity is often overstated and oversimplified. These digital assets, which are pegged to, e.g. fiat currencies such as the US dollar, come in different forms that drastically affect their suitability for illicit use. Centralised, collateralised stablecoins such as USDC or USDT are issued by companies that hold reserves and can freeze accounts (even if the funds went through a mixer), making them traceable and unattractive for large-scale criminal operations (crypto exchanges can also freeze or restrict illicit transactions - black listing). While decentralised stablecoins like DAI remove central control, their liquidity is limited, which restricts the feasibility of moving large sums. Algorithmic stablecoins, which rely on protocols rather than collateral, theoretically pose higher risks, but their small market size and history of instability reduce their practical impact.

In general, stablecoins offer benefits such as fast cross-border transfers, accessibility, and a degree of pseudonymity, but these advantages are constrained by regulatory oversight, monitoring, and blockchain traceability (all the features explained above for crypto-assets equally apply to stablecoins). Public discourse often overlooks these nuances. In practice, the dominant centralised stablecoins are heavily monitored and can be frozen, limiting their attractiveness for illicit actors, while decentralised options are less liquid, making large-scale abuse challenging.

The Bank for International Settlements, in its Bulletin No.111, accurately states:

“...the stablecoin market is dominated by centralised fiat-backed stablecoins, whereby only the issuer can mint new coins when they receive the fiat currency and burn the stablecoins when they pay out. The tree of wallets for any stablecoin can be traced back to its minting origins until it is burned. This centralised property also allows the stablecoin issuer to freeze the stablecoins in a wallet or deny their conversion to fiat currency.”

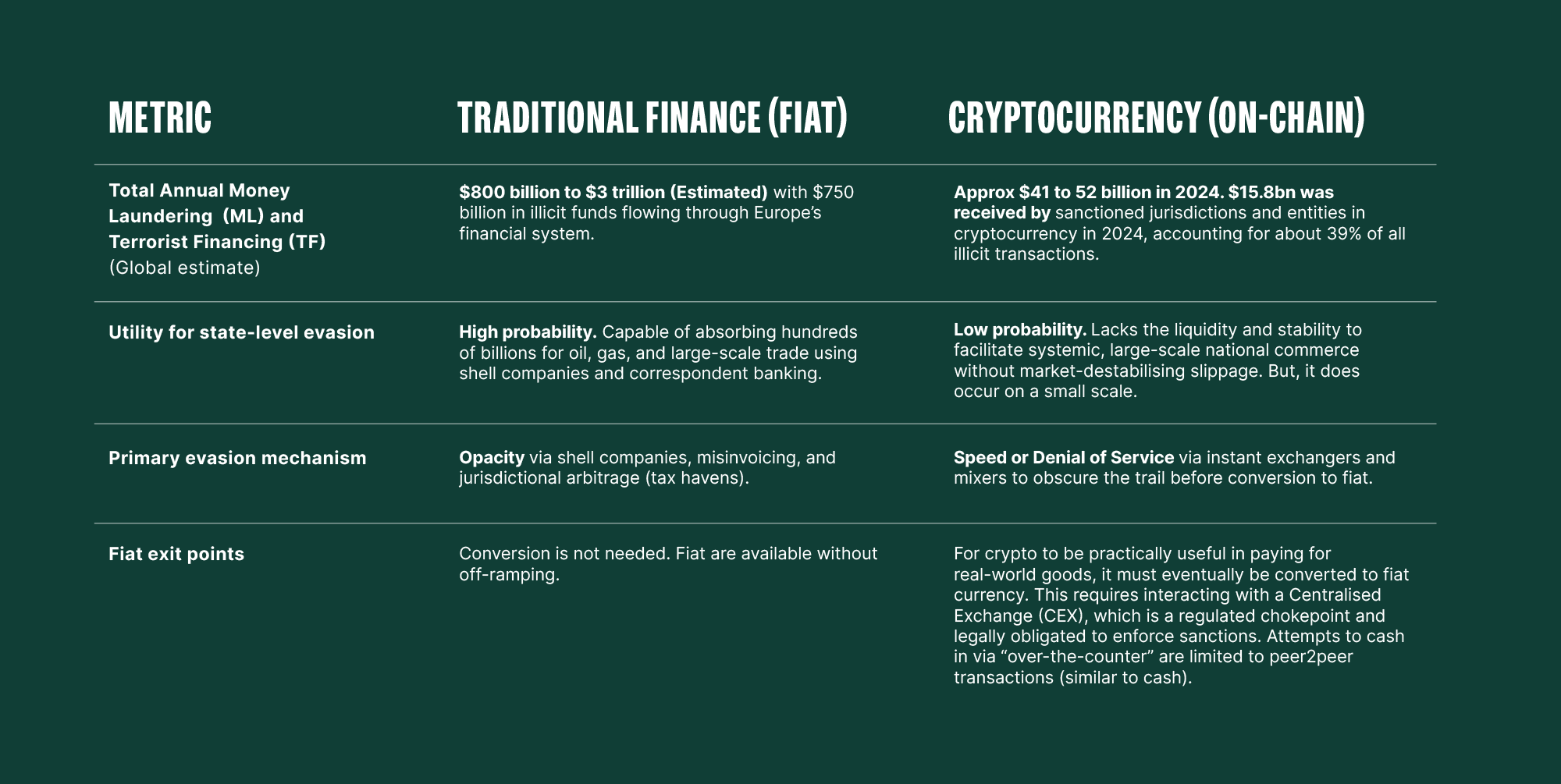

Insofar as crypto is described as a key means for sanction evasion, its share of the total illicit financial ecosystem remains comparatively small. Based on the available estimations, crypto illicit usage constitutes approximately 1–2%. Criminals, offenders, terrorists, totalitarian governments and other despicable actors are always on the hunt for alternative means and methods of ML and TF. Crypto and blockchain are indeed one of the new options that they can use. However, all the benefits and unique features of public nature, auditability and traceability described above, apply to sanction evasion. This is even so when decentralised exchanges are used, which is a speed bump but not a blocker. Therefore, simply saying that crypto is a main use for sanction evasion does not present the whole picture. Even though there are no complete, precise breakdowns for sanction evasion, let’s have a look at key facts and estimates showing that crypto usage is limited and illicit funds are not easy to off-ramp to fiat currencies and then spend.

The Targeted Update on Implementation of the FATF Standards on Virtual Assets and Virtual Asset Service Providers (2025) stated that traditional means, such as cash, are still the primary tools for ML and TF:

“Terrorist groups continue to utilise VAs, particularly to raise and move funds across jurisdictions, including by large-networked organisations (such as ISIL, AQ, and their affiliates). Nevertheless, the exact scale of the use of VAs for TF is still difficult to measure, and it appears that many terrorist organisations continue to mainly rely on traditional methods to raise, move, store and spend funds, such as cash, money value transfer systems, and hawala-type systems. Available evidence shows that the terrorist group (point 33 FATF)”

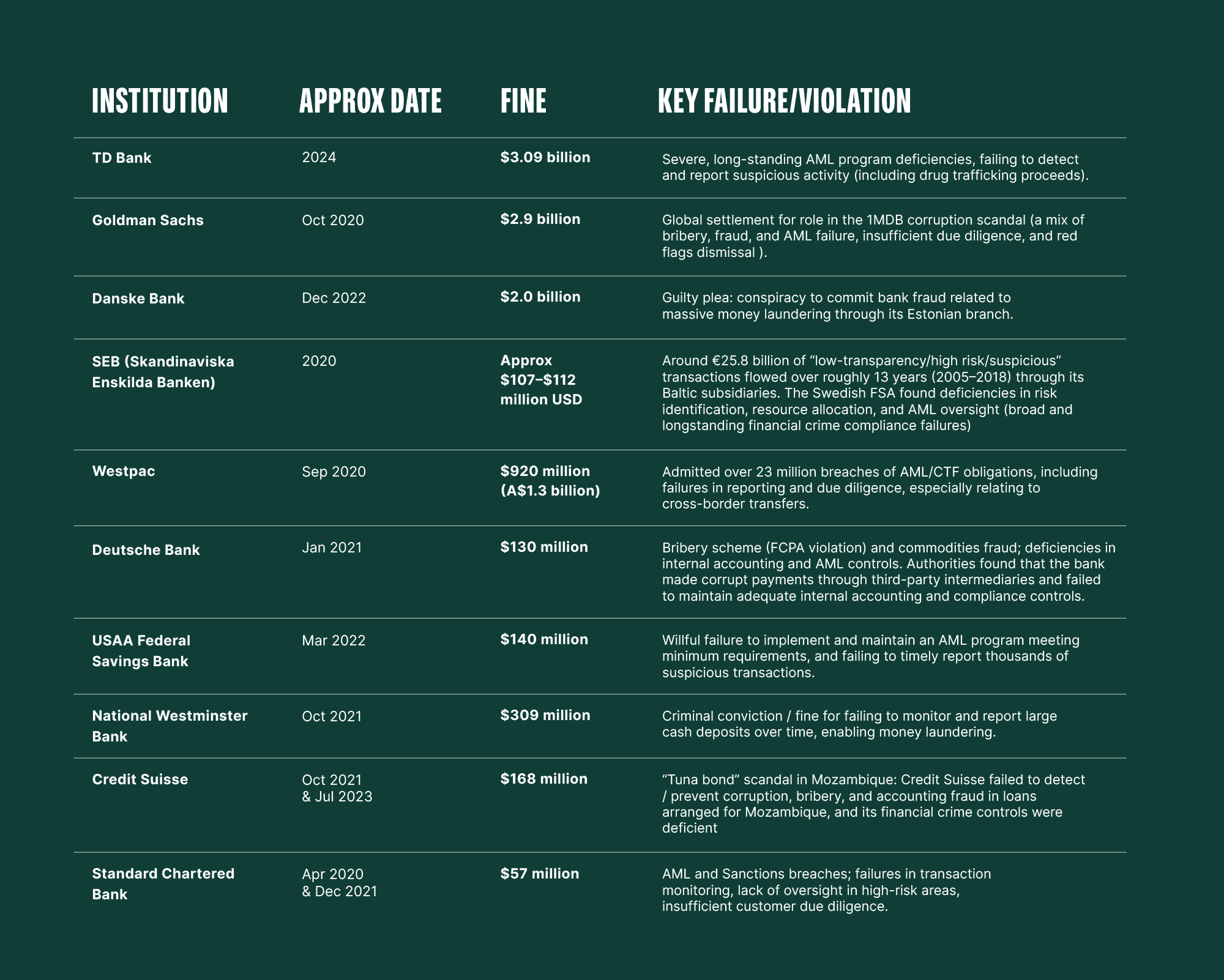

We explored the crypto industry as a key channel, but often forget to mention the extent of fines and abuse that happens via the TradFi channels that are more opaque and less accessible. Here are some examples:

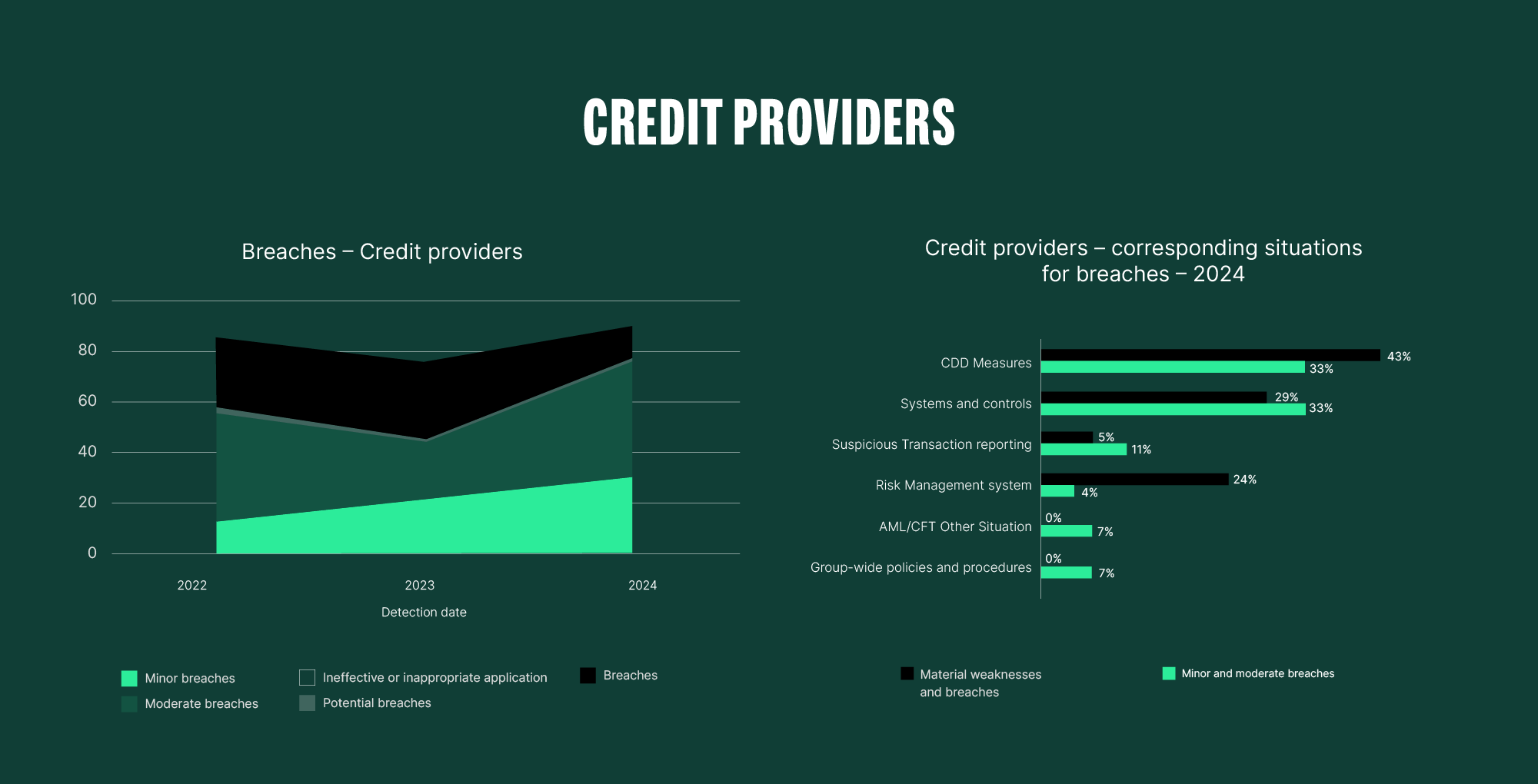

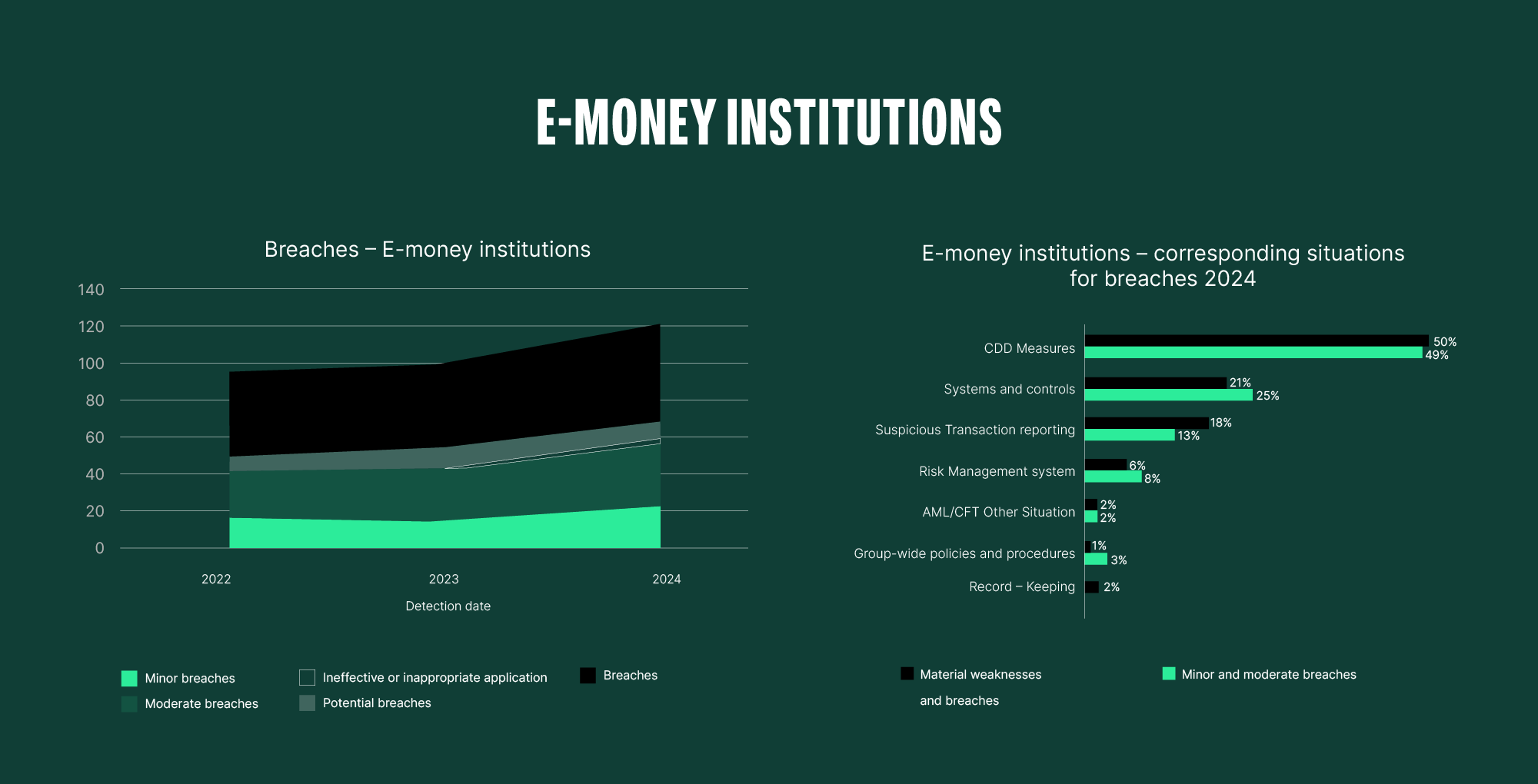

* European Banking Authority Report - Money laundering and terrorist financing risks affecting the EU’s financial sector (2025)

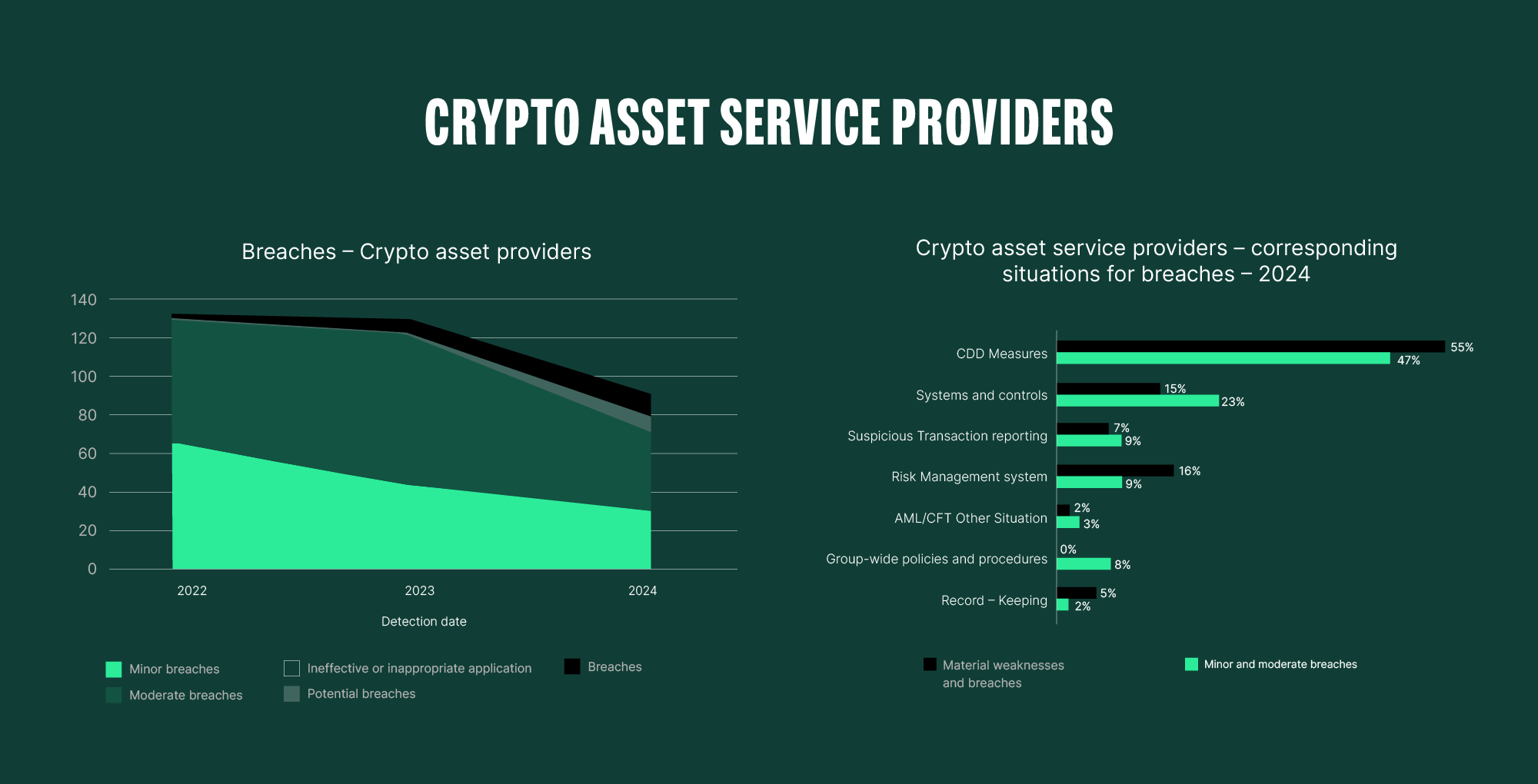

If we examine the breakdown for “AML/CFT Other Situations”, there is no staggering gap, but there are many shortcomings. It’s also noticeable that the level of breaches (minor, moderate, and high) decreased from 2022 to 2024 for the crypto sector, despite the still high starting point, which in fact now aligns with the levels of credit institutions and E-money institutions. This highlights that it is not technology itself but the human factor that is a problem.

The classification of crypto-assets as high risk while downplaying the features of blockchain technology and portraying the industry as the main channel for ML and TF is simply unjustified. Especially when the public statements are generalised and made without proper consideration and differentiation. As we’ve shown, the fact that the DeFi system is open, transparent, traceable and auditable, provides a tremendous advantage over the closed and isolated TradFi ecosystem. Never in the history of finance has the financial ledger been so public and transparent. Obfuscation mechanisms do provide barriers, but these walls are not insurmountable. Many forget to consider how traditional means continue to be abused and often unjustifiably blame new technologies like blockchain without a proper understanding and practical experience.

Overall, any new technology has the chance to be abused - and this is also true for the crypto industry. But ultimately, the unique characteristics that enable borderless financial monitoring and investigation actively discourage the abuse, making it harder for bad actors.

Let’s consider this myth demystified!

Disclaimer

This article is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer or recommendation. It does not constitute and cannot replace investment advice.

Bitpanda does not make any representations or warranties as to the accuracy and completeness of any information contained herein.

Investing carries risks. You could lose all the money you invest.

We use cookies to optimise our services. Learn more

The information we collect is used by us as part of our EU-wide activities. Cookie settings

As the name would suggest, some cookies on our website are essential. They are necessary to remember your settings when using Bitpanda, (such as privacy or language settings), to protect the platform from attacks, or simply to stay logged in after you originally log in. You have the option to refuse, block or delete them, but this will significantly affect your experience using the website and not all our services will be available to you.

We use such cookies and similar technologies to collect information as users browse our website to help us better understand how it is used and then improve our services accordingly. It also helps us measure the overall performance of our website. We receive the date that this generates on an aggregated and anonymous basis. Blocking these cookies and tools does not affect the way our services work, but it does make it much harder for us to improve your experience.

These cookies are used to provide you with adverts relevant to Bitpanda. The tools for this are usually provided by third parties. With the help of these cookies and such third parties, we can ensure for example, that you don’t see the same ad more than once and that the advertisements are tailored to your interests. We can also use these technologies to measure the success of our marketing campaigns. Blocking these cookies and similar technologies does not generally affect the way our services work. Please note, however, that while you’ll still see advertisements about Bitpanda on websites, the adverts will no longer be personalised for you.